Read the original article here.

LEONARD QUART: MARTIN SCORSESE HONORED AT BERKSHIRE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

By Leonard Quart

I recall when I first started watching Martin Scorsese’s films, how stunned I was by their pulsating energy, depiction of emotional alienation and formal boldness. I vividly remember the edgy, explosive “Mean Streets” (1973) and its gift for fusing realist and expressionist imagery to unsentimentally capture the codes and rituals that “the boys” followed on the streets of New York’s Little Italy where Scorsese grew up. It was followed a few years later by the striking “Taxi Driver” (1976) that was even more imaginative, violent and hallucinatory.

Scorsese’s films have tended to be neither political nor socially critical. His vision is primarily an aesthetic and psychological one. And “Taxi Driver” with its cinematic allusions, voice-over, restlessly moving camera, high overhead shots, semi-abstract sequences, slow motion and extremely tight close-ups of murderous protagonist Travis Bickle’s (Robert De Niro) mad eyes is exquisite. The film also brilliantly captures the sweltering night city of shadows, neon lights, shimmering shapes and manhole covers emitting steam, while never fully interested in creating a documentary or social realist view of the city during its darkest years. The city can be nightmarish, but the film is not about social collapse.

Scorsese’s emphasis is on one man’s personal hell and most of the film was shot from Bickle’s point of view, which is shaped by the dark ambience of film noir and the director’s own personal demons and fantasies.

I went on to teach courses analyzing Scorsese’s work and write essays and reviews on films like “Goodfellas,” “Gangs of New York” and “The Age of Innocence.” I have also always admired his smaller films like “Who’s That Knocking at My Door,” “After Hours” and “The King of Comedy,” and was less taken by his more impersonal, well-crafted, commercially successful and award-winning films like” The Aviator,” “The Departed” and “The Wolf of Wall Street.” In all his films—the smaller personal ones as well as the large productions—Scorsese’s distinctive use of editing and camera movement and gift for capturing his characters’ volatile emotions remains indelible. Of course, I also am moved by his passion for New York City, and even though he sees it through a dark lens, one always feels that his images convey the grandeur and energy of the city.

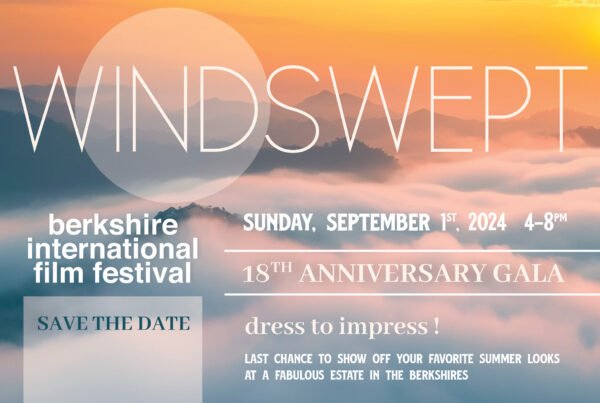

So when Kelley Vickery and Berkshire International Film Festival this year decided to pay tribute at a packed Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center to this great director by showing clips from his work and having him engage in an informal conversation with Pittsfield-born Kent Jones—the director of the New York Film Festival and director of a fine first film, “Diane”—I felt I had to attend.

Scorsese and Jones are friends and have worked closely together, which made their conversation natural and unforced. Their talk was structured around clips from films like “The Age of Innocence” (his adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel) with Scorsese, in his fast-paced manner, talking intensely about different aspects of the works.

Scorsese elliptically mentioned that before he made “The Age of Innocence,” he was feeling a sense of unfulfilled desire and loss—a key to the pain felt by the film’s protagonist, Newland Archer. He also said that he had grown up with traditional British films like “The Browning Version” and was interested in characters whose passions are constrained by tribal mores and rituals, though underneath they are bursting with feeling.

A clip followed from “The Red Shoes” (1948), a film that Scorsese fell in love with when he was 9 years old. Directed by his friend and mentor Michael Powell (e.g., “Black Narcissus”), the film’s rich, masterful color scheme plays as large a role as its romantic fantasy narrative focusing on a young ballerina torn between her love of a young composer and her commitment to dance. An imperious, obsessive impresario who insists that a dancer’s personal life has to be sacrificed to her art intensifies her conflict.

Scorsese founded the Film Foundation in 1990 and, through it, has funded many efforts at film preservation. One of them was restoring the heightened color of “The Red Shoes,” which had deteriorated. Scorsese spoke about his efforts at restoration with consummate mastery of all the technical aspects of making a film.

Other clips from Scorsese’s films were shown—one from “The Last Waltz,” which centers on the Band’s last performance, cutting and panning from one group member to another as they seamlessly connect musically to each other as one organism. Another two clips came from one of Scorsese’s masterpieces, “Raging Bull,” which deals with the champion boxer Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro in an Academy Award-winning performance). One was a choreographed boxing scene shot with the camera inside the ring that explodes onto the screen. The other scene uses point-of-view shots that capture LaMotta’s jealousy and volcanic rage building up as his was wife touched and kissed in an essentially chaste way by the mob boss.

As he always has done, Scorsese spoke about film with passion, encyclopedic knowledge and a belief in the greatness of the medium. When he was young, he believed that “cinema gave me a means of understanding and eventually expressing what was precious and fragile in the world around me.” He has achieved just that throughout his career, and BIFF provided a fitting tribute to this great artist.